In spring of 2024, I participated in a narrative hack-a-thon put on by my friends at ASU’s Center for Science and the Imagination. The gist of a “narrative hack-a-thon” is that you get a bunch of interesting thinkers together, with various expertise, you team them up with SFF writers, and you have them brainstorm a sci-fi story on a particular topic or question. This workshop asked us to come up with stories about the messy, historically fraught question of what the US should do with its nuclear waste.

The story I eventually wrote up is titled “Pursuant to the Agreement.” It’s an epistolary story, documents framed as a series of exhibits at a future Museum of the American Fracture. You can now read it in the book Our Radioactive Neighbors, edited by my colleagues Clark Miller, Ruth Wylie, and Joey Eschrich. The volume also includes stories by Justina Ireland, Carter Meland, and my friend and fellow solarpunk Sarena Ulibarri. This fiction is supplemented by about a hundred pages of essays explaining and exploring the mechanics of nuclear power, the history of NWM and siting policy, the complexities of seeking community consent. It’s all extremely thoughtful and informative. If you ever wanted to be able to impress your friends at dinner parties by mastering a grim and arcane but genuinely fascinating topic, well, this book could probably get you most of the way there!

There is also a really nifty supplemental facilitation guide featuring questions and activities that can be used to start conversations about the stories. Part of the role of the book, used in the larger 3CAZ series of community forums, is to help communities develop the imaginative capacities required to make hard collective decisions.

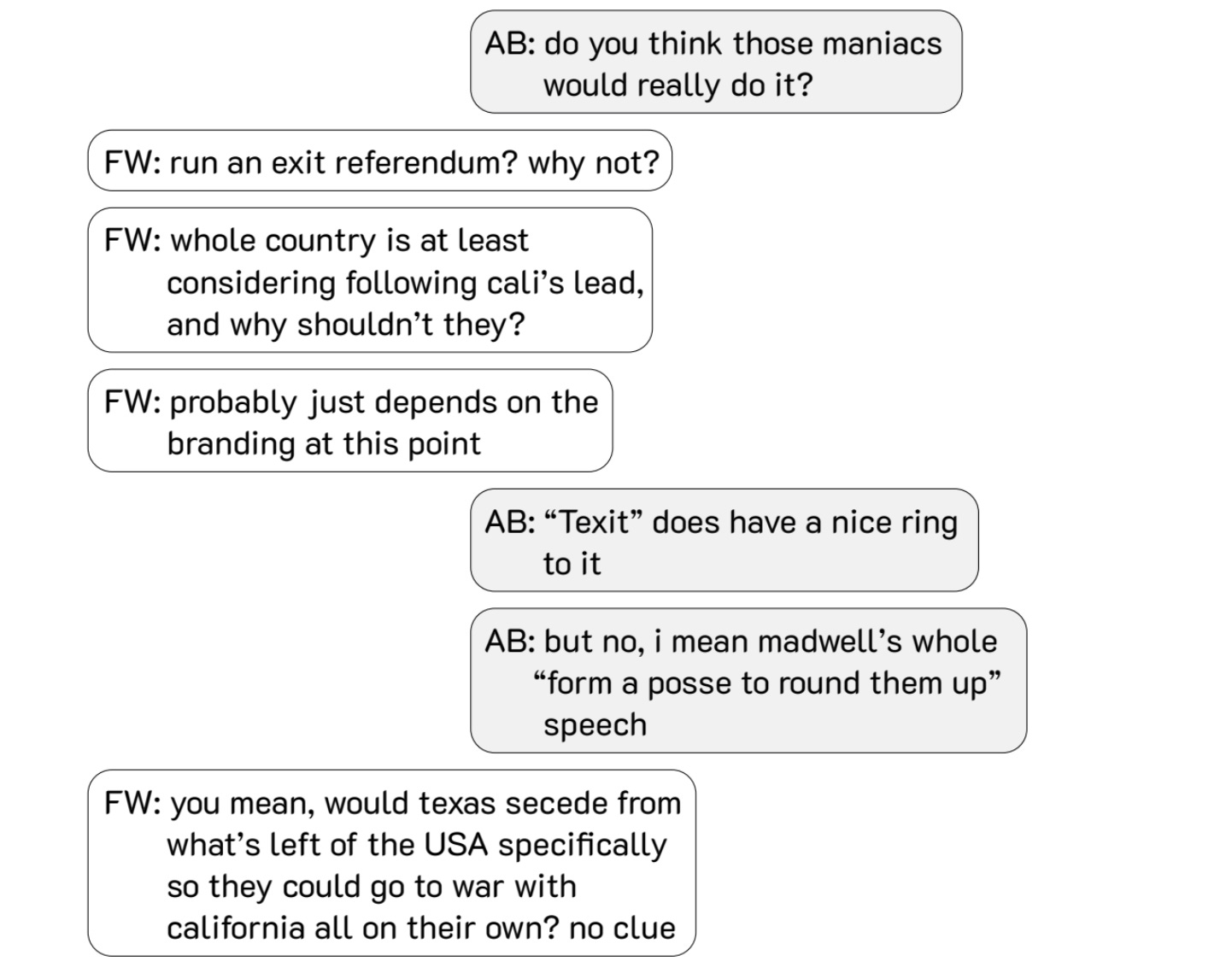

Here’s a snippet from “Pursuant,” from right around the middle of the story:

“Pursuant to the Agreement” sprawls across decades and generations and text genres. It features official documents, diplomatic communiques, text message conversations (see above), meeting transcripts, handwritten letters, and fuck-you emails, all held together with curator’s notes that give a 22nd century perspective on 21st century institutions, expectations, and foibles. It’s about trying to hold together a long-term project across an ever-shifting policy landscape and an ever-swinging political pendulum — in this case one swinging wildly enough to break its moorings and go careening off over the historical unprecedented horizon. Which, you know, relatable.

Check out “Pursuant to the Agreement” and all the stories and essays in Our Radioactive Neighbors: Collaborative Imagination, Community Futures, and Nuclear Siting Practices.